The Mimeograph Underground

In the age before copy machines, before the Internet, before “publish” became a button, a small hand-cranked machine quietly powered one of the most democratic publishing movements in modern history. The mimeograph was not elegant. It smelled of ink and solvents. It required stencils that tore easily and rollers that jammed. Yet, between the 1940s and the 1970s, this modest duplicator carried the same revolutionary spirit that later defined open-source culture.

The Machine That Made Communities

The mimeograph was simple but transformative. A typist or artist cut text and images into a wax stencil, wrapped it around an ink-filled drum, and turned a crank to press the ink through the stencil onto paper. The result was inexpensive and immediate duplication, hundreds of pages produced without a printing press or a publisher’s approval. According to National Geographic, this technology “democratized production, giving poets, students, and activists a way to distribute their ideas without permission.”¹

For many, this was the first time the tools of publication were in the hands of the creators themselves. In today’s language, the mimeograph was a kind of analog “publishing platform,” open to anyone who could afford paper, ink, and patience.

The Literary Underground

By the late 1950s, mimeograph machines had become central to a new kind of literary community. Beat poets, small-press editors, and fringe thinkers used the duplicator to print chapbooks, zines, and newsletters rejected by the commercial press. The result became known as the “Mimeograph Revolution,” a movement that blended artistic rebellion with technological improvisation.

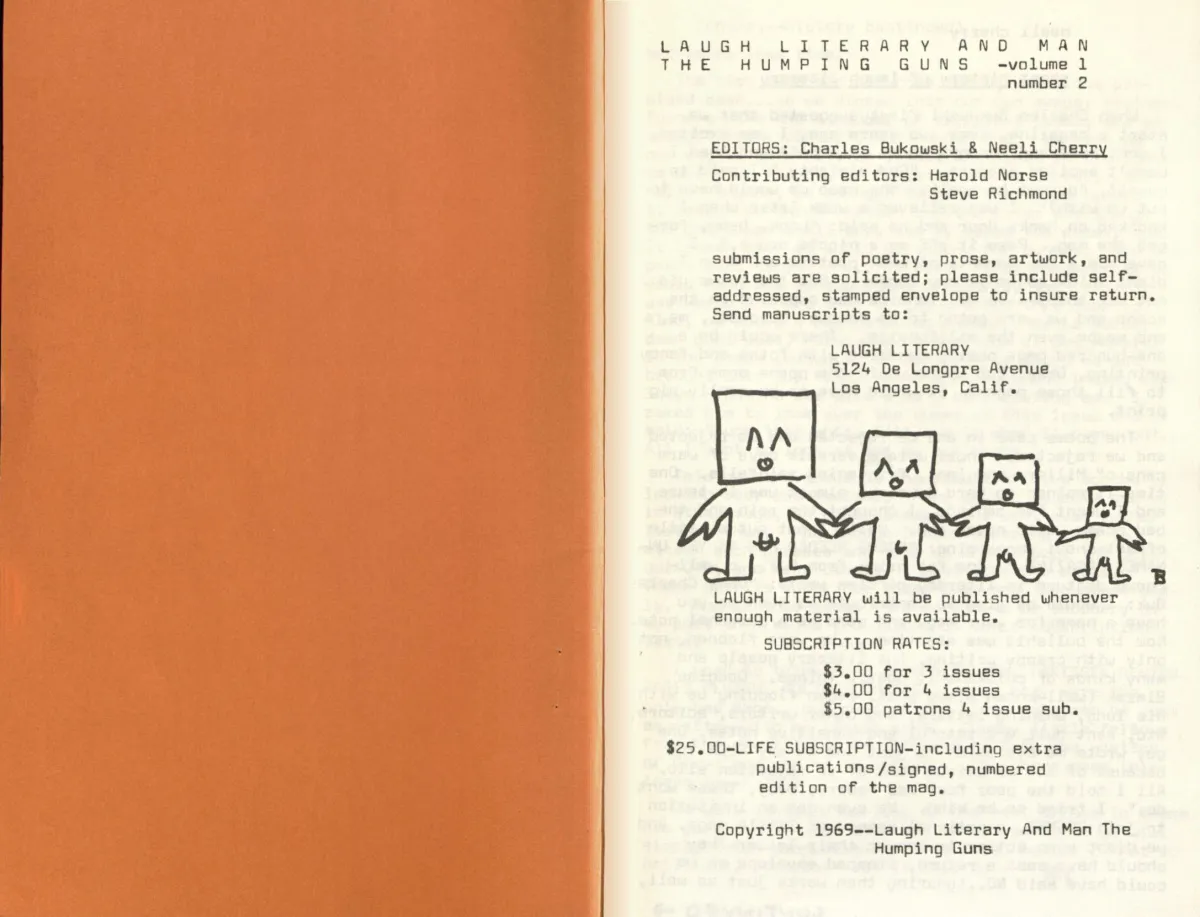

Charles Bukowski and Neeli Cherkovski’s Laugh Literary and Man the Humping Guns (1969–1971) is a landmark example. Working from Bukowski’s Los Angeles apartment, the two produced three mimeographed issues under the tongue-in-cheek imprint “Laugh Literary Press.” The first issue appeared in yellow wraps, thirty-two pages long, stapled by hand and filled with rough-printed poetry, satire, and self-mockery. The CSUN archives describe it as “a DIY literary magazine that attacked the establishment while parodying itself.”²

Bukowski’s editorial “manifesto” on the inside cover openly mocked the mainstream literary scene, calling out academic journals and curated poetry circles. He used the mimeograph both as a weapon and a form of freedom, a machine that let him publish without gatekeepers.

Fanzines and the Early Networks of Exchange

While poets used mimeographs for literature, other communities discovered them for shared imagination. Early science-fiction fans of the 1940s created “fanzines” with names like Futuria Fantasia and Amra, distributing them through mailing lists and conventions.³ Each was made with the same logic as open-source software: contributors wrote, traded, and remixed one another’s stories, building a self-sustaining network of amateur publishers.

By the 1960s, the same machines were printing student manifestos, feminist pamphlets, and political flyers. The mimeograph allowed marginalized voices, from campus activists to underground cartoonists, to bypass institutions of control and create micro-publics of their own.

Rough Aesthetics, Shared Ideals

Mimeograph print was never clean. Ink bled. Letters blurred. Stencils wore out. But those flaws became part of the aesthetic, proof of immediacy, authenticity, and human touch. As literary historian Jed Birmingham notes, the imperfections of mimeo printing “mirrored the urgency of the content,” and the medium’s low fidelity became its mark of honesty.⁴

What began as a technical compromise evolved into a philosophy of access and community. The mimeograph’s mechanical limitations encouraged collaboration and experimentation, what we might now describe as creative iteration.

The Code Before Code

Seen through a modern lens, the mimeograph functioned like early open-source software. It decentralized production, reduced barriers to entry, and encouraged collective creation. Each stencil was a piece of code, a set of instructions that, when executed by a crank and drum, produced identical “outputs” across dozens or hundreds of sheets. The operator was both programmer and publisher.

By the 1980s, mimeographs gave way to photocopiers and then digital publishing. Yet the culture they sparked, the belief that publishing belongs to everyone, remains the backbone of independent media today. The zines, blogs, and collaborative archives that fill the web echo the same values of access, community, and shared tools that once hummed from small offices, dorm rooms, and kitchen tables across the mimeograph underground.

Conclusion

The mimeograph may have been mechanical, but its legacy is conceptual. It taught creators to think like coders long before computers made that literal. Each sheet was an iteration, each crank a loop, each inked page a replication of human thought made physical.

In that rhythm of drum and stencil, the modern idea of open publishing was already turning.

Sources

National Geographic – “How an Obsolete Copy Machine Started a Revolution,” 2020.

California State University, Northridge – “Laugh Literary and Man the Humping Guns Collection,” 2023.

University of Iowa Special Collections Blog – “Spirit Duplicators, Early 20th Century Copier Art, Fanzines, and the Mimeograph Revolution,” 2021.

RealityStudio.org – “The Clark Nova Express: Horror Fanzines, the Mimeo Revolution, and William Burroughs,” 2015.

Wikipedia – “Laugh Literary and Man the Humping Guns,” “Mimeograph,” and “Mimeo Revolution.”